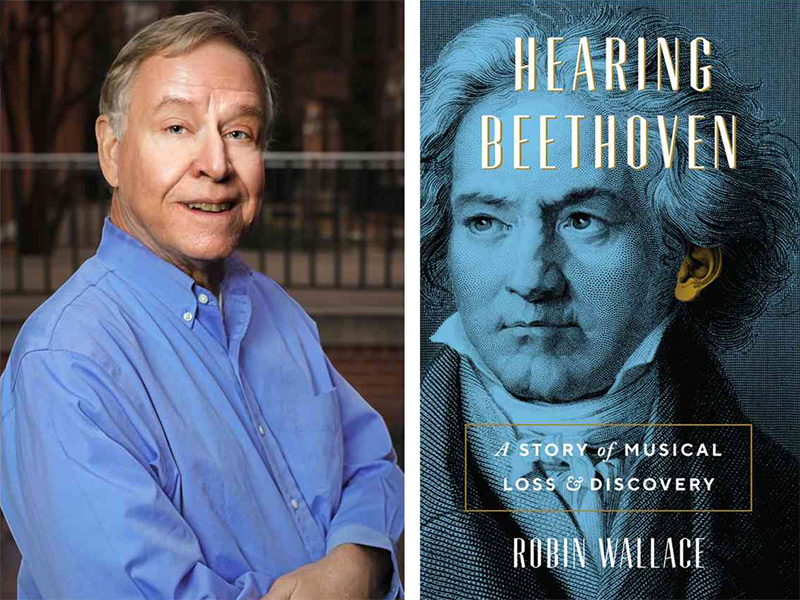

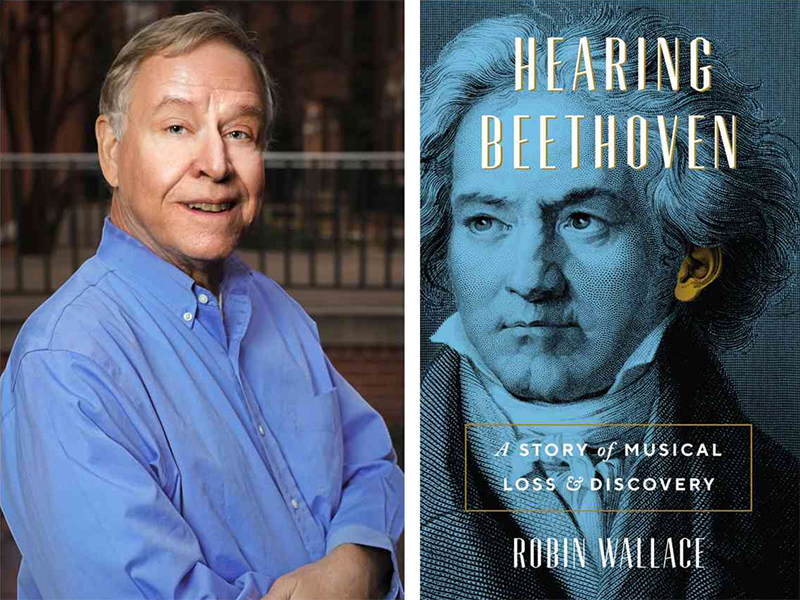

Baylor Musicologist’s New Book Relates Parallels in Late Wife’s, Beethoven’s Struggles with Deafness

Baylor Professor of Musicology Dr. Robin Wallace has written Hearing Beethoven: A Story of Musical Loss and Discovery.

Contact: Whitney Richter, Director of Marketing and Communications, Office of the Vice Provost for Research, 254-710-7539

Written by: Gary Stokes, Office of the Vice Provost for Research

WACO, Texas (October 4, 2018) – As a lifelong Beethoven scholar, Baylor musicology professor Dr. Robin Wallace felt he understood the great composer's epic struggle with hearing loss and how it had dominated his life and his art—until an intensely personal experience led him to a far deeper understanding of deafness than scholarship alone could ever supply.

In his new book Hearing Beethoven: A Story of Musical Loss and Discovery, Wallace elegantly overlays and interweaves his first wife Barbara's sudden partial, then total deafness with the great composer's inexorable descent into silence.

Long before Wallace met her, Barbara, who died from a stroke in 2011, was diagnosed in her twenties with a usually fatal type of brain tumor. After the tumor was removed surgically, she received intense radiation treatments through her ears to destroy any lingering cancer cells. Beating the odds, she lived for years, marrying her first husband and becoming pregnant. But she was soon widowed when her husband, a Marine, was killed in a helicopter crash. To add to her loss, soon after her husband's death she miscarried.

Years later, she and Wallace met, married and had two children. But in 2000, she awoke one morning to discover she'd become functionally deaf in her right ear. Doctors attributed it to the radiation treatments she had received years earlier. Then three years later she suddenly lost all hearing in her left ear, leaving her with the three percent of hearing remaining in her right ear as her only source of sound.

In the remaining years before her death, Wallace and Barbara adapted and persevered, battling her isolation, disorientation, depression and frustration. Time and time again, Wallace saw parallels with their experiences and Beethoven's trials some two centuries before. Just as Beethoven had used hundreds of "conversation books," in which people wrote their comments and questions so Beethoven could read them and then respond, Wallace, their children and friends wrote on pads and in notebooks to converse with Barbara.

And as the composer sought help through the technologies available to him in his day—elaborately constructed ear trumpets and an innovative resonator mounted on the top of his piano, for example—the couple sought assistance from modern technologies: an electronically amplified "pocket talker," hearing aids and, ultimately, a cochlear implant, which, after extensive and arduous nerve training, gave Barbara back some practical sense of hearing. His wife's deafness gave Wallace new and unique insight into the musician he had studied and written about for decades.

"For the next eight and a half years, I was probably the only Beethoven scholar in the world who lived with someone who was deaf and had the experience of that first-hand," Wallace said. "I think it didn't take long, even while my late wife, Barbara, was still alive, for somebody to suggest to me that I might be able to learn something about deafness from that experience that would enhance my understanding of Beethoven, and I began thinking about that."

Before losing her hearing, Barbara had been a registered nurse, a vocation she found rewarding in large part because it was complementary to her love of people. But deafness had made it impossible for her to continue. Worse, the miscarriage appeared to have put her desire for children beyond reach as well. Even in that, Wallace found parallels with Beethoven. He writes:

Nursing was Barbara's job, but she defined her vocation not by her work but by her relationships with others. She had also longed to be a wife and a mother, and when she lost her first husband and her baby within weeks of each other, her work as a nurse was no consolation. After she and I learned she had a uterine septum that made it impossible for her to carry a baby past nine weeks, we unhesitatingly spent thousands of dollars on treatment that was not covered by insurance. Jennifer's birth in December 1991, and Jeremy's a little over two years later, were no less miraculous than Beethoven writing the Ninth Symphony while unable to hear.

Wallace says that a secondary motive for writing the book lies in his hope to set readers straight on a number of misconceptions and myths about the composer. First, he likely never grew completely deaf—there is evidence that he had at least a faint sense of hearing until his death. And it's unlikely that he ever cut off the legs of his piano, as has been conjectured, so he could feel the vibrations of the music through the floor. Nor was Beethoven strictly bound to written score: he was brilliant at improvisation, which was a hallmark of his personal performances. Wallace says that in many ways, and for all the challenges he encountered in life, Ludwig van Beethoven constitutes a major milestone in the development of music.

"Beethoven in a sense marks a watershed in music history," he said. "Before Beethoven, if you had asked most people who is the primary creative artist in music, is it the composer or is it the performer, they would have said, 'It's the performer, of course; that's the person who is actually doing the music. The composer is a facilitator who helps them do it, and often, the composer and the performer are the same person.' [But] since Beethoven, most people in classical music would answer the question the other way around—the composer is the primary creative artist; the performer is the facilitator whose job it is to convey what the composer wrote as accurately as possible."

The Wallaces' story ably demonstrates that, whether sudden or gradual, and though devastating and disrupting, hearing loss needn't be the defining element for those who encounter it.

"[Beethoven's] life and his music nevertheless remained whole: single entities touched, but not defined, by deafness," Wallace said. "Beethoven did not overcome deafness; he found himself through and along with it."

Hearing Beethoven: A Story of Musical Loss and Discovery is published by University of Chicago Press. To view a summary and reviews of the book, and to pre-purchase, click here.

A book launch event celebrating the release of Wallace's book and Singing the Congregation, a book by Baylor ethnomusicologist Dr. Monique Ingalls, will be held October 8, 2018, at 5:00-6:30 p.m. in Jones Library 200 (Campbell Innovative Learning Space). The event is co-sponsored by the Baylor School of Music and the Crouch Fine Arts Library.