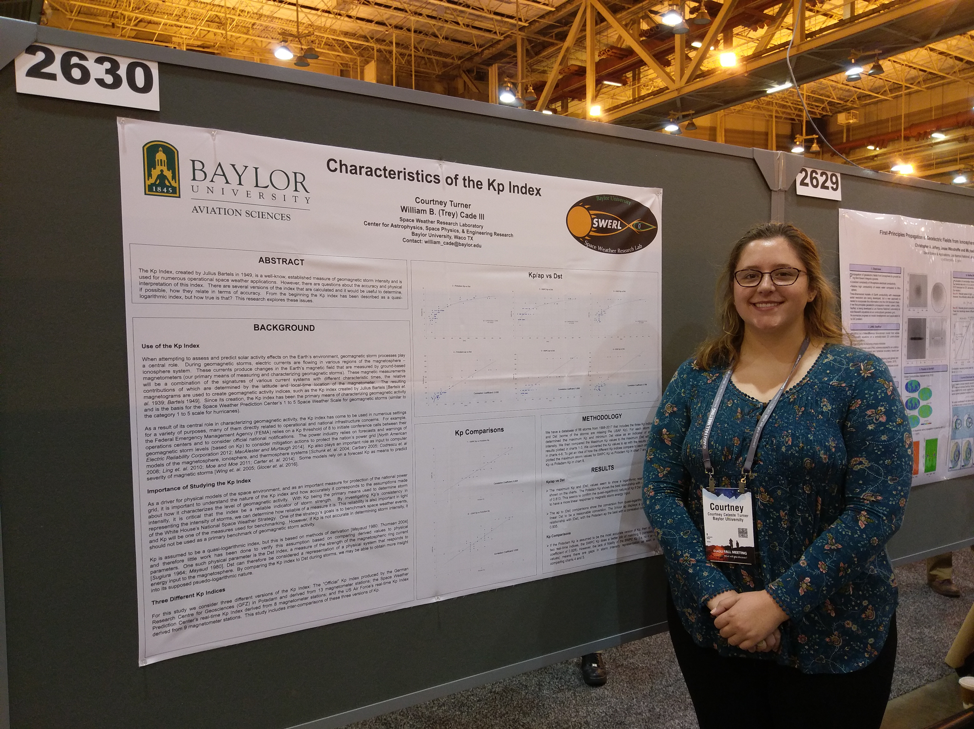

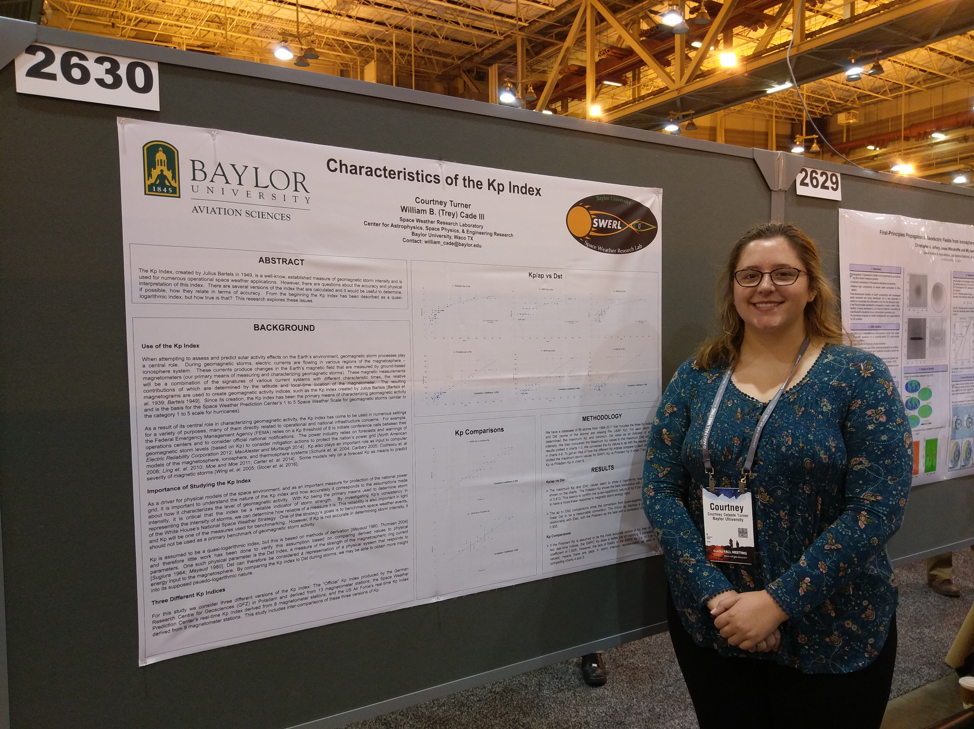

Baylor Senior Presents Solar Storm Research at Space Weather Conference

Aviation sciences major Courtney Turner studies potentially devastating geomagnetic storms.

Contact: Whitney Richter, Director of Marketing and Communications, Office of the Vice Provost for Research, 254-710-7539

Written by: Gary Stokes, Office of the Vice Provost for Research

WACO, Texas – Baylor senior and Granbury, Texas, native Courtney Turner presented research findings at the 2017 fall meeting of the American Geophysical Union. Held December 11-15, 2017, in New Orleans, the event is the largest Earth- and space-science conference in the world. Turner's research focuses on measurement and classification of solar storms, which present a serious and underappreciated threat to our technology-dependent way of life.

On any bright day the sun may seem to be a warm, cheery, yellow disk. In reality, however, it is a fiery sphere spewing vast, invisible clouds of electrically charged particles into space. Normally the Earth coasts through this “solar wind” with little obvious effect, other than causing the fascinating curtains of neon-like light in the polar skies known as auroras.

But occasionally the sun launches a mammoth burst of particles strong enough to wreak havoc on electrical systems and devices here on Earth. In 1989 a solar flare caused a massive power outage in Canada, and in October of 2003 a solar storm struck with enough energy to disable a third of NASA's satellites. The most intense solar storm ever recorded occurred in 1859. Known as the Carrington Event, it delivered severe electrical shocks to telegraph operators, sparked fires, and made the northern aurora visible as far south as Hawaii. Today, with our 21st-Century reliance on electrical devices and power systems, a Carrington-scale event would cause unfathomable disruption and devastation.

“One thing that I think is very interesting is that a lot of people don't even know this [threat] exists,” Turner said. “They just go outside and think, 'Oh wow, what a beautiful day,' and then we could have [a storm] like this and …,” Turner shrugged.

While a solar storm even close to Carrington magnitude hasn't struck our planet in modern times, it is virtually certain one will. Turner's research is aimed at bettering our understanding of a real-time measure of activity in the Earth's always-changing geomagnetic field known as the “Kp index.” Developed in the 1930s, the index is determined in part using data from a network of magnetometers placed around the world. The index ranks geomagnetic activity on a scale of zero to nine, with nine being the most active. Any level over five is considered a storm.

Because many conditions and processes can cause the geomagnetic field to fluctuate, scientists still don't fully understand precisely what the Kp index represents and if they are using its data to assess and predict storm strength appropriately.

“The uncertainty comes in with the physical interpretation,” said Dr. Trey Cade, head of Baylor's Aviation Sciences program and Director of the Baylor Institute for Air Science. “We measure it and we know we're measuring changes in the Earth's magnetic field, but … what does that mean in terms of how big the storm is? … We provide warnings and forecasts to officials and agencies that need to take action. If we are not measuring and categorizing storms correctly, it would be like telling Florida they are going to get hit with a Category 2 hurricane when it is really a Category 5.”

Turner is hopeful that her work with the Kp index will pave the way for more timely and accurate geomagnetic storm assessment.

“If we find any discrepancies in the Kp, or in how it's used, we can look for other options or for other ways to interpret the data and … figure out the best way to use this resource to predict. evaluate and disperse the information we have about storms,” she said.

Cade added, “Or we may even come up with completely new ways to measure storms. The technology we have now is much better than the technology that was available in the 1930s when this index was developed. Maybe now there are better ways to do this.”

In addition to her space weather interests, when Turner graduates in May 2018, her Aviation Sciences degree also will have prepared her for a potentially lucrative career as a professional pilot.

“I'd like to stay in the science side of it if I can,” she said. “I really like monitoring the storms just to see what goes on and how it affects the Earth and satellites,” she says. “But in the near term I'll probably stay in Waco and [flight] instruct and build my flight hours.”