Tri-institutional study of remote Amazonian tribe yields surprising insights into origins of cultural preferences for music.

Dr. Alan Schultz, Assistant Professor of Anthropology and Global Health contributed as a co-researcher to a recent study of perceptions of music among an isolated Amazonian tribe.

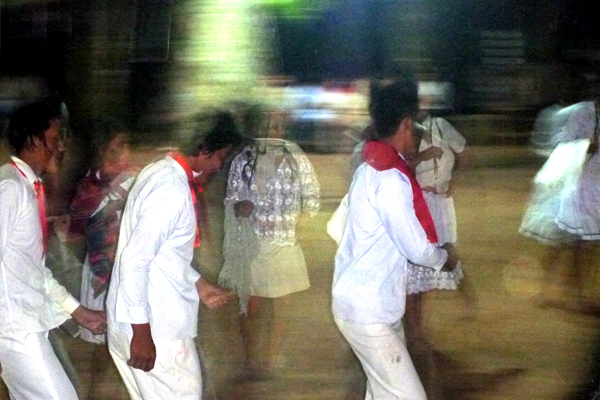

contributed as a co-researcher to a recent study of perceptions of music among an isolated Amazonian tribe. WACO, Texas - Baylor assistant professor of anthropology and global health Dr. Alan Schultz contributed as a co-researcher to a recent study of perceptions of music among an isolated Amazonian tribe. Schultz joined lead researcher Dr. Josh McDermitt of MIT's Department of Brain and Cognitive Sciences, and Brandeis University colleagues Dr. Eduardo A. Undurraga and Dr. Ricardo A. Godoy on the National Science Foundation-funded project. Publication of the study's findings last July in the journal Nature generated brisk debate in the scientific community and drew broad coverage by the national media. The study sought to uncover the source of an observed preference in Western culture for musical consonance, or harmony, over musical dissonance and lack of harmony. The source of this preference has remained ill-defined, with many observers asserting that human physiology predisposes humans to favor harmony. Others, Schultz and colleagues among them, argue that one's environment exerts a greater influence over such preferences than is commonly recognized. The question is yet another facet of the enduring "nature versus nurture" debate, and one that is made even more difficult to study by the scarcity of societies that have not had extensive exposure to non-native music, and yet are also reasonably accessible to researchers. For their research project, the team selected the Tsimane (chi-MAH-neh), an indigenous group that inhabits a scattering of villages along the Maniqui River in the lowlands of northeastern Bolivia. In addition to their cultural isolation and limited accessibility by canoe, the Tsimane were deemed especially well suited to the project because harmony is virtually absent in their native musical tradition. The researchers played a wide assortment of tones and chords—some harmonious, others jarringly discordant—to over a hundred Tsimane and recorded their responses. Time and time again the Tsimane judged neither harmonious nor inharmonious sounds to be more or less acceptable. This stark indifference led the researchers to infer that, assuming Tsimane physiology to be typical of humans in general, groups having a preference must derive it substantially from culture. Even more convincing was the finding that Tsimane living progressively farther upriver expressed proportionally greater indifference: the greater their isolation, the greater their indifference. While the overall findings didn't surprise Schultz, the conclusive nature of the evidence did. "I was surprised by how clear it all was; I think we all were," Schultz admitted. "What was really striking was this gradient of exposure: the Tsimane with greater exposure versus Tsimane with little exposure—you could see it all in how the data tracked with exposure." That trend lent the team an element of confidence researchers seldom enjoy. "When we talk about good research and what builds that case for causality, this gradient of effect is critical to that question. It speaks strongly to the idea that this is likely what's really going on."